USA women open Volleyball Nations League against Thailand

May 13, 2024

June 30, 2022

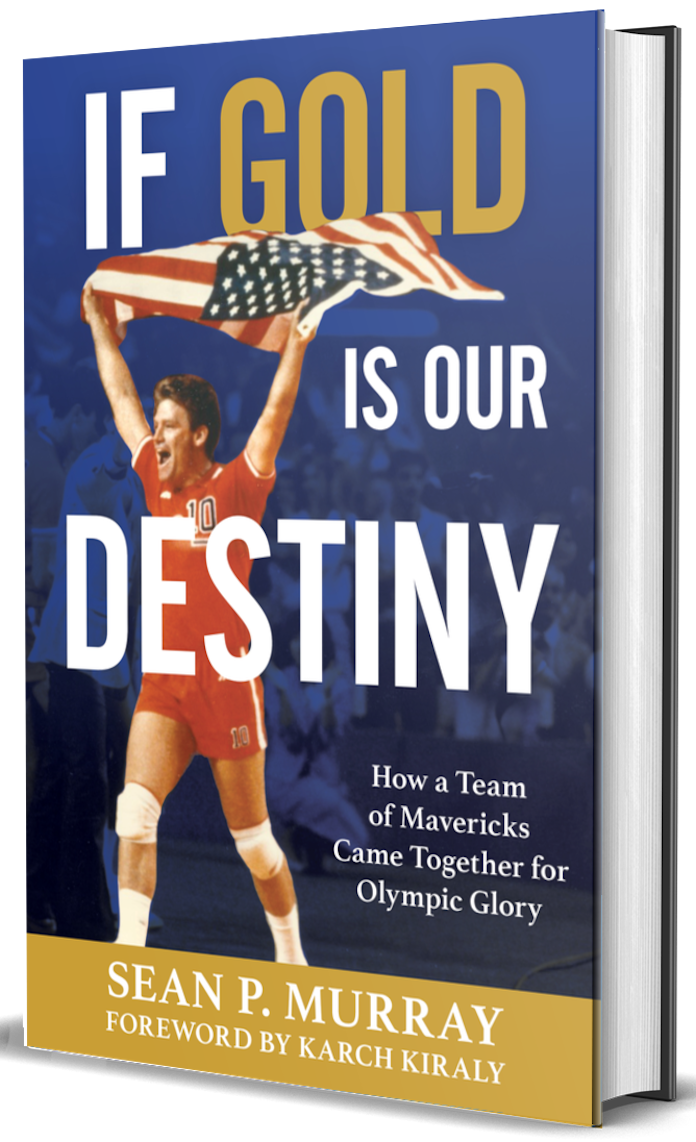

Sean Murray’s father, Don, was one of the team psychologists when the USA men won volleyball gold in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. So for many reasons, that team, which broke all sorts of volleyball barriers for the USA, has always been special to Murray.

As it turned out, the bulding of that squad was years in the making with quite a few twists and turns and no shortage of drama, all of which are well documented by Murray through thorough research and interviews.

Murray’s book, “If Gold Is Our Destiny,” comes out next month. Links to a virtual launch party and how to buy it follow this chapter, which was provided by the publishing company Rowman and Littlefield.

The chapter is called “The Straw That Stirred Our Drink:”

The countdown to Los Angeles had begun. As the calendar turned to 1984, everything surrounding the National Team seemed to quicken in pace. Each match took on more meaning, and the competition for playing time intensified. Players lived in fear they would suffer an injury, preventing them from competing at the Olympics, and Beal noticed that smaller injuries suddenly seemed to “heal†much faster than normal. No one wanted to give the coaches any reason to reduce playing time or keep them off the team.Â

The Olympic Games were highly anticipated in Southern California. The press kept the public informed as the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee prepared each venue and sport for the upcoming competition. Essentially L.A.’s “hometown†team, the U.S. men’s national volleyball team had never before been so celebrated, or so scrutinized, so much so that the team psychologists worried if they might crack under pressure or if the sudden attention would go to their heads. They were rock stars, and volleyball was hot.Â

To prepare for the competition, the team scheduled a series of friendly matches against the Cubans in February. Timmons was fighting for a spot on the team and running out of time to demonstrate his value. On the flight to Havana, Neville sat next to Timmons.Â

“Red, I love you. I want you to be on this team,†Neville said. “But you have to convince two other coaches: Tony Crabb and Doug Beal. If there is anything you can do to solidify your spot, you have to do it now.â€Â

The Americans had asked for the matches to be played in a large arena, to better prepare both teams for the Olympic atmosphere in Los Angeles. Cuba complied, scheduling the matches for the 15,000-seat Coliseo de la Ciudad Deportiva in Havana.Â

During the first match, Buck was having trouble with a sore ankle and Timmons replaced him. In one play early in the match, Dvorak set the ball to Timmons from the back row, a rarity in the Americans’ offense. Dvorak usually focused on setting the ball to the outside hitters. Hitting from the back row is tricky, requiring near perfect coordination and timing between the setter and hitter.Â

Timmons played the ball perfectly from the back row, executing a devastating kill. A short time later, Dvorak did it again, and Timmons was again perfect, catching the Cubans off guard. Dvorak and Timmons were in sync, and Dvorak, realizing Timmons was lighting it up, returned to him again and again.Â

Marlowe watched from the bench with amazement. He immediately recognized that Timmons had upped his game. Hitting from the back row was a game changer. The Cubans couldn’t stop him. Nothing could stop him. “We have to give Red a new nickname,†Marlowe implored his teammates on the bench. “We should nickname him ‘God.’â€Â

That night Timmons kept his roommate, Berzins, up most of the night as he replayed the match in his head, going over again and again what trans- pired on the court that day and what it might mean for his chances to make the team. Timmons was so jacked up he barely slept in anticipation of playing again the next night.Â

The following evening, Buck started as usual, but when Timmons subbed in, he once again lit up the scoreboard, proving his performance was no fluke. Now Dvorak had another solid option. He could set a high outside ball to Powers or Sunderland, do a quick set to Buck, set Karch on the “swing†attack, or set Timmons in the back row. That was a revelation. Now every player was an offensive weapon, and the opposition had no idea what to expect. The potential of the American team appeared limitless.Â

“Originally, our back row offense depended upon Hovland,†said Beal. “When he left, we didn’t have the hitters there, until Timmons.â€

By the fourth match in Cuba, Timmons not only became a starter, he played the entire match. And he played the entire fifth and sixth matches, too. Six months earlier, he hadn’t even made the travel squad, and now Beal couldn’t take him off the court.Â

For well over a year, the competition between Marlowe and Wilde for the backup setter position had been heating up. With Dvorak getting most of the playing time with the starters, Marlowe and Wilde, just as Timmons had, needed to take advantage of every opportunity. Whenever Beal turned down the bench and called out their name, they had to be ready to go, physically and mentally, especially if they got a chance to play with the starting group.Â

A glossy magazine called Countdown to Los Angeles, produced by USA Volleyball to build interest in and support for the team, contained a blurb about each player. Wilde’s profile read, “Wilde has the finest pure technique of the setters and is quicker than heat lightning. He’s the best on the team at setting the bad pass and has excellent range on defense.†On the other hand, Marlowe’s note read,“ Marlowe has the unique ability to draw the best out of everyone around him. He is a leader and a strong competitor.â€Â

What was notably missing was a single word about Marlowe’s skills, either his setting talent or technique. He could set, but as the magazine noted, and as the staff and even the players sensed, his most valuable role was that of a leader.Â

“Chris was the straw that stirred our drink,†says Karch.Â

“Chris had a way of getting the players on the court to feel something,†said Timmons, “to play harder, to want to win.â€Â

For the last year, the coaches knew they had a very difficult decision to make between Wilde and Marlowe. Do they go with the younger more physically talented setter in Wilde or the more experienced, charismatic leader in Marlowe?Â

“Chris always had the chatter on the team, retelling stories,†recalled Timmons. “He was a great historian of volleyball, and everything revolved around Chris. He wasn’t the best athlete; he wasn’t the best setter. Rod was a better athlete and a better setter, but Chris was the ‘hub’ of the team.â€

As Neville recalled, “The three coaches agreed that we could only carry two setters and we had three good ones—each with unique strengths: Dusty was the best tactician, having an instinct to know who to set and when. . . . Wilde was the best athlete: quick; gymnastic; pure setting technique . . . always eager to please. He would give you the shirt off his back.Â

“Marlowe was the best leader,†continued Neville. “He made everyone around him better.Â

“As coaches we bantered around what was ultimately best for our chances in the Olympics? We created ‘what-if?’ scenarios. If Dusty went down and was out, who would best replace him? We debated and concluded Wilde would be the best because of his extraordinary athletic tools. We had to make decisions [based] on the worst-case scenarios.â€Â

Responsibility for the decision ultimately rested on Beal.Â

In late March 1984 Beal designated a day for personal evaluation meet- ings with each player. None of them knew if this was just a routine check-in meeting so the coaches could give the players feedback or whether one or more players might be cut from the squad.Â

Dvorak met with the coaches first, and Marlowe was supposed to come in that afternoon, the tenth player evaluated. But around 10 a.m. Beal phoned him and said, “Come down early. I’m going to meet with you now.â€Â

Marlowe suspected something was up. “Why was I getting called out of order?†he wondered. Marlowe drove to the team offices and saw Beal, a somber look on his face, standing in the parking lot to meet him. He feared the worst.Â

Beal greeted him at his car, something he’d never done before, and the two went to the coach’s office. As Marlowe entered, he saw Neville and Crabb sitting, both bearing the same heavy look. As Beal began talking, the other two coaches looked down, their eyes fixed on the ground.Â

Beal had told the players he had already met with that he planned to cut Marlowe. They hadn’t liked it and told Beal he was making a mistake, imploring him to change his mind. Beal had tired of hearing that over and over and, dreading the meeting with Marlowe, called him in out of order, determined to get it over with.Â

Beal told Marlowe he was being cut from the team. He explained what a difficult decision it was and then walked Marlowe through his thought process, explaining that he had decided to keep Wilde because he was a setter who could also come in as a back row sub, dig and pass balls, and contribute that way. Beal also explained that in the event Dvorak was injured and couldn’t play in the Olympics, Wilde simply gave the team a better chance to win.Â

It was a challenging decision for the entire coaching staff and an emotional one for Beal, whose friendship with Marlowe went back a decade, to when they had been teammates on the National Team. It was one of the most difficult things Beal ever did as a coach. “I had a ton of respect for Chris,†Beal said. “The fact that he had come back. The respect he had from the other players, and his role on the team.â€Â

Although Marlowe had always known he might be cut, he had never allowed himself to admit it. Usually the most talkative guy in a room, for the first time in his life he just didn’t say anything, surprised but not shocked, and just listened. He knew there was no way to talk his way back on the team. Neville and Crab kept their heads down as Beal continued to explain the decision.Â

As the meeting came to an end, Marlowe finally spoke up. “Gentleman,†he said, “I think you’re making a mistake, but I’ll respect your decision. I know you’re trying to do what’s best for the team.†The whole experience was gut- wrenching and emotionally painful for everyone involved, and now it was time for it to end. No use dragging it out. They all stood and shook hands. As Beal walked him out to the lobby, he told Marlowe, “Look, stay ready. Keep in shape. If something happens, we will need you.â€

When Marlowe sat down in his car, alone, the full weight of the news hit him. He was devastated. His Olympic dream went all the way back to the 1975 team that failed to qualify in Rome. He had gone through a great deal since then—giving acting a try, dealing with the death of his father, and trying to make a comeback as the oldest member of the team. And now—pfft—it was all over.Â

Word traveled fast, and Wilde was ecstatic when he learned the news. His Olympic dream was finally within his grasp. He thought back to his very first volleyball tournament at age ten, when on the drive home he told his dad he would one day play on the Olympic team. Now, here he was, seventeen years of hard work later, on the cusp of realizing that dream.Â

Neville later debriefed Wilde and was blunt, saying, “Rod, you are the only one who is happy about this. . . . They [the team] do respect you [but] they love Marlowe.Â

“You were chosen because of your great athletic skills and would give us the best chance to win if Dusty faltered. So, here is the deal: Don’t say a word. Don’t criticize, compliment, give directions, joke. Play like you can. The boys are angry—mostly at Doug and, to maybe a lesser degree, me—but they will take it out on you, so keep your mouth shut and just play.â€Â

Many of the players were shocked and disappointed that Marlowe was cut. “The whole point of Outward Bound was to create the best team dynamic, the best trust, the best connections,†said Karch.“ Chris Marlowe fostered that more than anyone, hands down. That’s why cutting Marlowe confused us so much, it sent the direct opposite message of all we were trying to build.â€Â

“When they made the choice to cut Chris, it was a mistake,†said Timmons.“ It is not the best player versus best player, it was the player who can help the team. And Chris was the player who could help the team.â€Â

The following Monday, instead of going to practice, Marlowe went to his part-time Olympic job at the bank to tell his coworkers that he hadn’t made the team. He broke down in tears, unable to get the words out.Â

Marlowe packed up his belongings, said goodbye to his best friend and roommate and the couch he called home for two years. He moved back to L.A. and got a job tending bar at the Malibu Chart House.Â

He was still “The Big Cy,†one of the living legends of beach volleyball in Southern California, two-time winner of the Manhattan Open. And now, with the Olympics around the corner, and the biggest volleyball tournament in the world coming to his hometown, he was tending bar. His friends kept calling him and stopping by. Everyone wanted to know, “What happened?â€Â

It was too painful. He wanted to go into all the details and explanations; the Outward Bound experience and the time in Poland when he rallied the team and all the stories, but the most gregarious guy in the room was once again silenced. He simply answered, “I got cut and I’m an alternate.†That usually ended the conversation. People understood.Â

After he got over the shock of being cut, he picked up the pieces of his life. Ever the optimist, he decided to stay in shape, just in case. He continued to work out every day, running and lifting. He kept his volleyball skills sharp by playing at the beach.Â

A good friend from San Diego, John Schroeder, was doing TV work at the time. He reached out to Marlowe to do a segment about his time on the NationalTeam and his experience getting cut. They took half a day to do some stand-ups and interviews.Â

“What are you going to do now?†Schroder asked.

“Well, go back and resume my real life,†answered Marlowe.

“Are you going to continue to work out?â€

“Yes, I will. I feel somehow it’s all going to work out.â€

Many of Marlowe’s teammates were crushed too. “Part of our ‘soul’ was missing,†said Karch. They all felt his absence. The coaching staff anticipated a letdown after cutting Marlowe and had intentionally done so just before a series of matches with Czechoslovakia so the team would have to focus on volleyball instead of their feelings.Â

Czechoslovakia had not qualified for the Olympics that year, but as a big, physical team, they resembled some of the teams that had. The United States won all three matches comfortably and, as Neville hoped, the matches provided Wilde a chance to prove himself on the court and to be embraced by the team.Â

With the roster now down to thirteen players, Beal had one more big decision to make to trim the team down to the twelve players who would walk into the Olympic opening ceremony together on July 28. He rotated all thirteen players on the court to help with his decision and give the second team playing time and confidence.Â

The coaches knew that the powerful Soviet team would be favored to win the gold medal. The team, coached by Viacheslav Platonov, was the reigning world champion and Olympic champion, and nothing in their recent play indicated they were ready to give up their titles.Â

Beal had scheduled a series of matches in early May against the Soviets to gauge his team’s progress before they began final preparations for the Olym- pics. In many ways, the team’s performance in these matches would be a test of three years of hard work and tough decisions that started with moving the national training center from Dayton to San Diego, all the way through Outward Bound.Â

They warmed up with a two-match stop off in Bulgaria, winning both matches handily. Beal continued to experiment and in the second match started Timmons and Buck together for the first time, providing both size and more opportunities for Timmons to score out of the back row. At their best, Timmons and Buck proved to be slightly better than Salmons and Duwelius, the other two middle blockers. The victories provided a confidence boost and sweet revenge for the devastating loss at the World Championships in Argentina two years earlier. It was obvious the team had come a long way since then. But the real test remained ahead. The Americans had not defeated the Soviets in sixteen long years, since the 1968 Olympics, when many of the players were barely in grade school.Â

The team traveled to Kharkov, in what is now Ukraine, for matches on May 8, 10, 12, and 13. While physically dominant, the Russians could also be predictable, almost machinelike in their tactics and strategy. Over the previous year, Tony Crabb had traveled to Europe multiple times to watch the Russians, compiling a detailed scouting report. Beal, Neville, and Crabb had already spent years studying and learning from Platonov. Now, with Crabb’s insights, they put together a game plan to exploit the weaknesses of the Russian system.Â

When the team walked onto the court in Kharkov on May 8, 1984, something was different. They were not intimidated. For the first time they faced the Soviets with confidence. They believed they could win and they believed in each other.Â

The two teams were evenly matched in terms of talent, and they battled it out for the first four games. With the match tied at two games each, there was a five-minute break before the fifth and final game. When the Russians returned to the court, Platonov and his staff flashed concerned looks and the normally fiery coaches appeared distracted.Â

Beal could sense right away that something was wrong. Seeing the worried looks on the faces of their coaching staff, the Russians seemed to lose fire. In the final game, the full effect of the new “American system†finally began to break the Russians down. With Karch and Berzins positioned to receive serve, and Dvorak executing the swing offense and Timmons flying toward the net from the back row, everything was falling into place for the team. The Americans won the fifth and decisive game in dominating fashion, 15–6. The win shook the foundations of the volleyball world.Â

“The Soviets did not lose even in friendlies,†said Beal.“Platonov did not like to lose at all.†The Americans had studied the Soviets for years. “They had taught us so much about volleyball,†said Beal.“ And now we were throwing it all back at them, with some new twists.â€Â

Beal and the players erupted into celebration. The victory, coming in Russia’s backyard, was a huge accomplishment, validating everything the team had been working toward for the past three years.Â

At that moment, while celebrating on the court, Beal looked around at his players. He began to believe that his team was the best in the world, and he could see that the players were beginning to believe the same thing. “We were going nuts in the locker room,†recalled Karch. “We are on our way. We are close to arriving now. We just beat the number-one team in the world on their home floor.†But the celebration didn’t last long.Â

Immediately after the game, Beal was pulled aside and informed that the Soviet Union had just announced a boycott of the Los Angeles Olympics, citing “chauvinistic sentiments and an anti-Soviet hysteria being whipped up in the United States.†The decision had everything to do with politics and nothing to do with sports. In 1980, the United States had boycotted the Moscow Olympics due to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan—this was simply payback.Â

Beal surmised that the Russian coaches had likely been informed during the break, before the last set, and it was the shocking news of the boycott that had caused the distraction. After the game, Platonov approached Beal and offered his congratulations, but his face was ashen. “We are not going to Los Angeles,†he told Beal, confirming what the U.S. coach had already feared.

Beal wasn’t yet certain whether the boycott was just a threat or a reality. He conferred with Neville and Crabb, and together they decided not to tell the team of the Soviet boycott right away and let them enjoy the victory while they gathered more facts.Â

The following day, May 9, was a national holiday in Russia commemorating the end of World War II in Europe, and the Russians had planned a joint appearance for both teams at a local memorial. After practice that morning, just before they left for the memorial, Beal gathered his team and informed them of the boycott that now included several other Eastern Bloc countries and Russian allies.Â

“We were looking forward to a bigger showdown at the Los Angeles Olympics,†said Beal. “That’s what we wanted. That’s what our players wanted. That’s what our country wanted. We wanted to beat the best team at the best tournament. Now that was impossible.â€Â

It was a major letdown. As athletes, the Americans felt terrible for their Russian counterparts. They were rivals, yes, but the U.S. players respected the Russians and knew how hard they worked for the opportunity to play in an Olympics. And they felt a sense of loss for themselves too. They desperately wanted to compete and win against the best in the world in Los Angeles. Without the Soviets and other Eastern Bloc countries competing in Los Angeles, they feared it wouldn’t be the same.Â

Still trying to absorb the news, the team joined the Russian coaches and players at an impressive World War II memorial in Kharkiv. During the ceremony, Beal could see Platonov breaking down in tears. Beal couldn’t figure out if Platonov was crying over the boycott or the memory of the war. Platonov, who had become a personal friend, later told Beal that his father had been killed in the war near this memorial.Â

Suddenly, volleyball didn’t seem as important. Beal had great respect for Platonov and Russian volleyball. In many ways his goal over the last eight years had been to create a team as dominant as the Soviets and to establish the United States as the best team in the world. Now, standing next to Platonov and taking in the gravity of the moment, he had a sense that this journey was about something bigger than volleyball.Â

Ideally, sport is supposed to transcend politics. Athletes are not soldiers. The tradition and purpose of the Olympics, going all the way back to the ancient Greeks, was to bring nations and city-states together, in the spirit of peace, to participate in friendly, yet spirited, competition.Beal believed strongly that athletes should not be prevented from competing for political reasons.Â

But it wasn’t up to Beal or Platonov. Greater forces were in motion, and the Russian and American athletes were at the mercy of global politics.Â

Over the following days, Beal observed the Russian team as they came to grips with the boycott. Several Russian players had originally planned on retiring after their gold medal victory in Moscow in 1980 but had rededicated themselves to the team with the singular hope of competing in Los Angeles. Now, after four additional years of hard work and training, that dream was over.Â

Beal realized another lesson, that “a team or individual shouldn’t place all their focus on one goal. Sure, the gold medal and playing in the Olympics is important, but the goal is the process, not the end result.â€

A few days after the boycott was announced, the Russians hosted the U.S. players and coaches for a “real American barbeque,†albeit with a distinctly Russian flavor.There was lamb sautéed in vodka, caviar, fresh meat, fresh fruit, and shots of vodka all around. In between rounds of drinks, the players would all take a sauna, sweat out the vodka, then come back to the party to eat and drink more. The Russians were intense on the court, but they also knew how to throw a party. As the two teams bonded, both sides were more disappointed than ever that they would be unable to compete against each other at the Olympics.Â

Over the years, Beal and Neville had grown close to one of the Soviet scouts, an older man who did research for the Soviet team. Neville, always thinking of “what-if †scenarios, asked Beal, “What if the U.S. had a scout that scouted our own team? What would they tell us? What is our vulnerability?†Of course, they didn’t have such a scout, but now wondered, since the Olym- pics were off the table, might they get some information from their old friend?Â

Beal and Neville invited the Russian scout to their room to discuss life and volleyball. Although Neville was a teetotaler, Beal and the scout shared a few obligatory shots of vodka, and then they asked their Russian friend what he thought about the new “swing offense.â€Â

“Aw,†he said with a smile. “It’s a spaghetti bowl. We have no idea where your hitters are going.â€

Beal and Neville smiled. If the Russian couldn’t figure it out, the American system was working. Even if there had been no boycott, they now believed the U.S. was likely the better team.Â

In the remaining matches, the Russian intensity and competitiveness so evident in the first match never materialized. The Russian players just didn’t have their heart in it, and the United States dominated. Nevertheless, it was good practice and preparation for the Olympics.Â

One of the highlights during the first few matches in Russia was the improved play for Wilde, not only setting but also coming in to play the back row. Wilde was in a tough situation because Marlowe was so well liked, and for some of his teammates the disappointment of losing Marlowe lingered, but just as Neville had counseled, he handled himself well and delivered exceptional performances on the court. No longer sharing time with Marlowe, Wilde got more reps with the starters and played his best volleyball, appearing to justify Beal’s decision.Â

In the last game of the last match in Russia, the match firmly in hand, Wilde subbed in to replace Dvorak. It was mop-up time. The ball was on the Russian side of the court. Oleksandr Sorokolet, one of Russia’s top outside hitters prepared to spike.Â

Wilde was near the net. Although he normally blocked on the right side, in this instance Wilde, who often tried to do more than he needed to on the court, moved over to be a third blocker on the left side, something the team hadn’t practiced. Maybe it was his way of proving to the guys he was up to the job.Â

He leaped in the air, arms extended, in an attempt to block Sorokolet. As Sorokolet came down, a little out of control, his foot landed under the net across the center line, a not uncommon occurrence and still within the rules, but directly under Wilde.Wilde came down awkwardly, landing on Sorokolet’s foot.Â

Crack!Â

“You could hear the bones breaking from the bench,†said Neville. “It sounded like something I remember hearing in the forest when I lived in Montana. In the late winter, when the snow gets too heavy on the limbs of trees, they’ll snap and it creates an echo. It’s an ugly kind of sound, especially when it’s a guy’s leg.â€Â

Wilde heard the crack and went down hard on the floor but didn’t feel any pain at first. Buck hunched over him on his left side and Karch did the same on his right. Still in shock, Wilde attempted to lift his leg off the floor, but his leg below the break didn’t move, flopping down on the court. Wilde had suffered a double fracture in his lower leg, breaking both the tibia and fibula, the bones between the knee and ankle.Â

“I looked at my leg and there was a huge gap in my sock,†said Wilde. The trainer for the U.S. ran onto the court to assess the injury.

“Rod, this is bad,†the trainer said.

“Yes. I know. I can see it,†Wilde said, still in shock. As the severity of the injury set in, Wilde’s thoughts went immediately to the impact on the team. “Thank God this wasn’t Dusty,†he said to Karch and the other teammates around him.

Wilde was crushed inside. He feared his Olympic dream might be over.Â

Beal and the players felt terrible for Wilde, but suddenly they needed a backup setter for the Olympics. Everyone knew the obvious choice was halfway around the world pouring margaritas and chatting up the locals at the Malibu Chart House.Â

Wilde’s injury wasn’t exactly front-page news in the United States, and in those days it wasn’t easy to send a message across the globe. A telephone call from Russia to the United States was an expensive and complicated affair involving international operators, and the coaches couldn’t get a call through. Later that night, Karch tried to call Marlowe to give him a heads-up and tell him to get ready. Although Karch was the youngest player and Marlowe the oldest, they were close.Â

Karch wasn’t able to reach Marlowe either, but he was able to reach his own family and relay the message to his father. Laszlo Kiraly immediately understood the gravity of the situation. He recognized the positive impact Marlowe had on his son, and as much as he respected Wilde’s volleyball skill, he hadn’t agreed with Beal’s decision to let Marlowe go. Las promised his son that he would reach Marlowe and let him know what had happened.Â

Back in Los Angeles, the team’s success in Russia was featured in the Los Angeles Times that week. Marlowe was happy for his teammates but couldn’t help feeling a sense of loss. Just as he closed the front door on his way to work the evening shift at the Malibu Chart House, he heard his phone ring. He paused for a moment, wondering if he should go back and answer it, then turned around, went back inside, and picked up the phone.Â

The voice on the other end of the line spoke with a thick Hungarian accent.Â

“Hello Cy,†Laszlo greeted him.Â

“Hi, Las,†Marlowe answered, recognizing the voice and Hungarian accent right away.Â

“Have you heard zee newz?†Las asked.Â

“Yeah, we are beating the Russians, pretty amazing,†Marlowe said, sounding deflated.Â

“No, not zat!†Las interrupted. “Rod Wilde just broke hiz leg. And if zat Beal doesn’t fuck you over again, you’ll be back on zee team!â€

Marlowe was stunned.“ At that moment I wasn’t sure what it all meant,†he said. He felt terrible for Wilde, but at the same time he felt a measure of guilt that Wilde’s misfortune might, for Marlowe, turn out to be a good break and open a door for him to return to the team. He also couldn’t help but wonder if Wilde’s injury would heal in time for the Olympics.Â

He got as much information as he could from Las before going to work. That night, as he tended bar, he tried to process it all.Â

“It was a strange feeling,†said Marlowe. “I was in a daze. I probably drank more cocktails than I served that night.â€Â

The next day Marlowe answered another phone call, this one from Beal. “I want you to come back on the team,†said Beal.

Marlowe already knew his answer. “I don’t want to come back unless you can guarantee me a spot on the team for the Olympics. I can’t go through that again,†he said.Â

“I can’t guarantee that,†said Beal. “If Rod is able to come back, you might be off the team again.â€Â

Marlowe just couldn’t bring himself to agree to return on those terms. It would be too emotionally painful to be cut again, and this time around it might come just weeks or days before the Olympics. Beal and Marlowe went back and forth. Finally, Beal offered a grim prognosis:“Look,†he said.“He has a broken leg and it’s pretty bad. Chances are he is not coming back.â€Â

Marlowe thought for a moment and agreed to return.The next day he drove down to San Diego, moved back into his buddy’s house, and reclaimed his spot on the couch.Â

A short time later, when the team reconvened in San Diego, Beal invited the players to vote for a team captain and Marlowe was voted in unanimously. The players sent Beal a message: “You cut him, now he’s our captain.â€Â

In Chris Marlowe the players now had a captain to unite and inspire them.Â

The straw was back in the drink.

***

Here is a registration link for the virtual launch party.

And here is the link to the publisher’s site and how to pre-order.